Sidney Evans

In the December 8, 1876 issue of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the victim’s name appeared for the first time as “Evans, Sydney (colored), Hudson and DeKalb avenues.” The next day, the Eagle described “Scenes at the Morgue” on page 4, reporting how “Dr. Shepard and Dr. Miner were engaged in making autopsies on the bodies of the negro Evans and John Hickey, in the dissecting room.” Just a few paragraphs below in the same column, the report read “Of the seven remaining bodies at the Morgue, two, Sidney Evans, negro, Hudson avenue near DeKalb, and Michael Cassiday, 475 Adelphi street, have been identified. The county will bury the other five.”

On December 9, 1876, The New York Daily Tribune wrote of “THE GREAT CATASTROPHE” in Brooklyn which had “A Death-Roll of Almost Three Hundred.” Listed in alphabetical order, some of the names on this roster included the age of the victim as well as a specific address; and for Sidney Evans, we find the following description:

EVANS, SYDNEY, Hudson, near DeKalb-ave. This was the body of a colored man, but it could be distinguished from the others with difficulty. He was identified by relatives, who recognized peculiar marks upon the clothing. County Physician Shepard made a post-mortem examination of this body yesterday and found that death was due to asphyxia. The body was removed to Hudson-ave.

All of the local New York newspapers — namely the Herald, the Times, the Tribune, the Sun and the Eagle — published the same information on Sidney Evans as written above. Even though Evans’ body was identified by “relatives,” the names of these individuals were not reported in any of the aforementioned newspapers; nor do we know his exact place of residence, his age or other vital statistics. In fact, his name appeared on the Official List of Those Reported Missing of Whom No Information Can Be Obtained which was published in the December 27, 1876 issue of the Eagle.

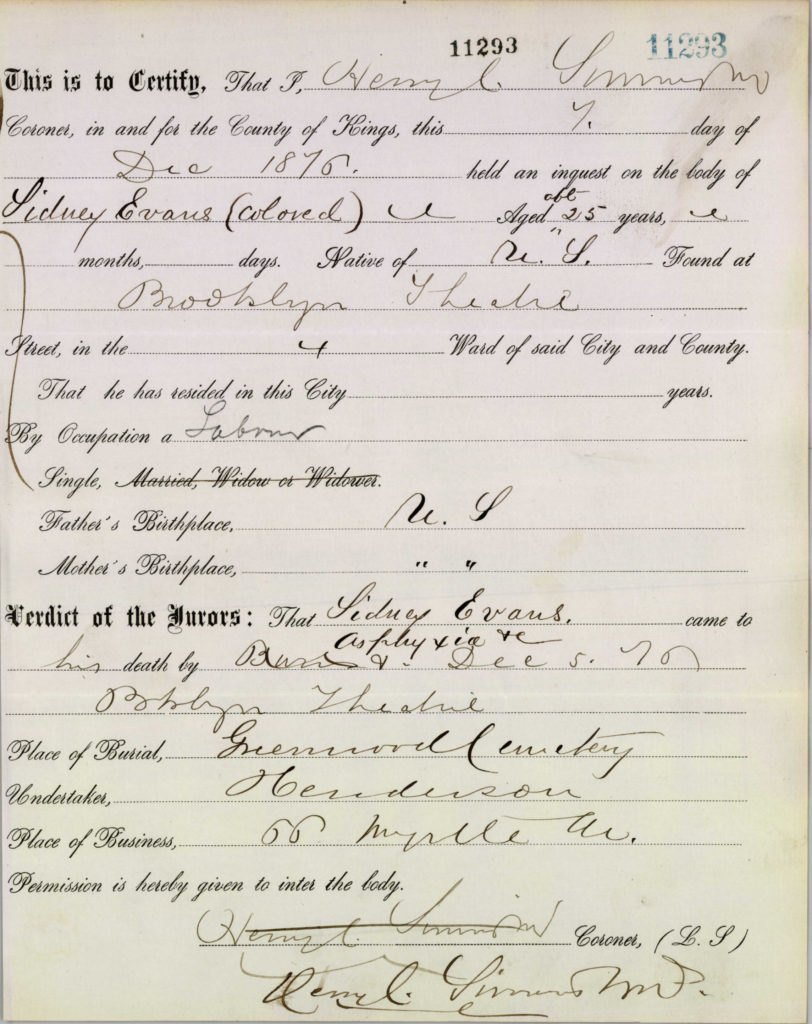

Coroner Simms, who issued death certificates to all the victims of the fire, spelled the name as “Sidney Evans”. The certificate of death shows the place of burial as The Green-Wood Cemetery. According to the official cemetery records, Sidney Evans’ remains were interred on December 9, 1876, in the mass grave along with 102 unidentified victims. However, his surname on that day was recorded incorrectly as “Lewes or Luers.” It is probable that on this cold December day the funeral director’s penmanship faltered from writing numerous of documents for each victim brought to the cemetery; the person transcribing this information likely misspelled the surname “Evans.” There is no other explanation, as no other person’s remains with the given name “Sidney” were interred on that day.

On December 10, 1876, the New York Times reported that “After the eleven unrecognized bodies had been removed it was found that two identified bodies were still at the Morgue, one of these was the body of Sidney Evans, the colored young man who was identified on Thursday, and whose friends could not afford to bury him.” This explains why he was buried among the unidentified in a common grave purchased by the City of Brooklyn, but this report also hints at a possibility that Sidney Evans did not have any close family in Brooklyn, or in the New York area. Perhaps, his origins lie outside of modern New York City.

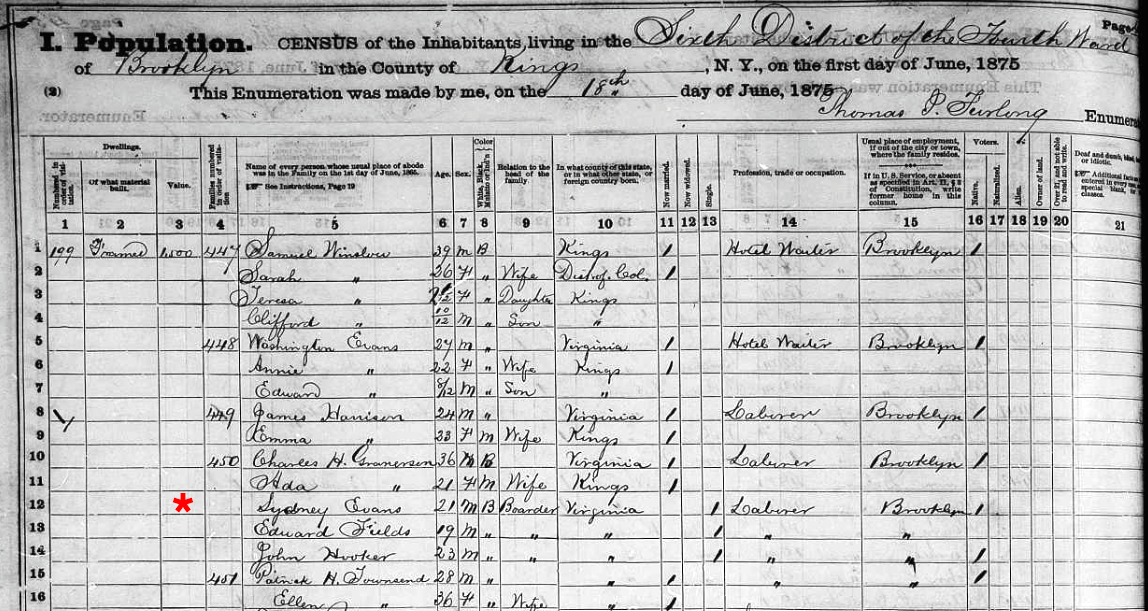

A year before his demise, when the 1875 New York State Census was enumerated, we find him as Sydney Evans living at No. 1 Lawrence Place in Brooklyn (image above). He was boarding with two other individuals (19 year old Edward Fields and 23 year old John Hooker) in the household of Charles H. Granerson. According to the census record, Evans was 21 years old, born in Virginia and single. Like most of the residents on Lawrence Place, Sidney Evans was employed as a laborer in Brooklyn. He lived in a mixed neighborhood of immigrants from Ireland and England. The building where Evans lived housed many African-Americans who hailed from Virginia, including the 27 year old Washington Evans (line 5), whose relation to our Sidney cannot be established at this time.

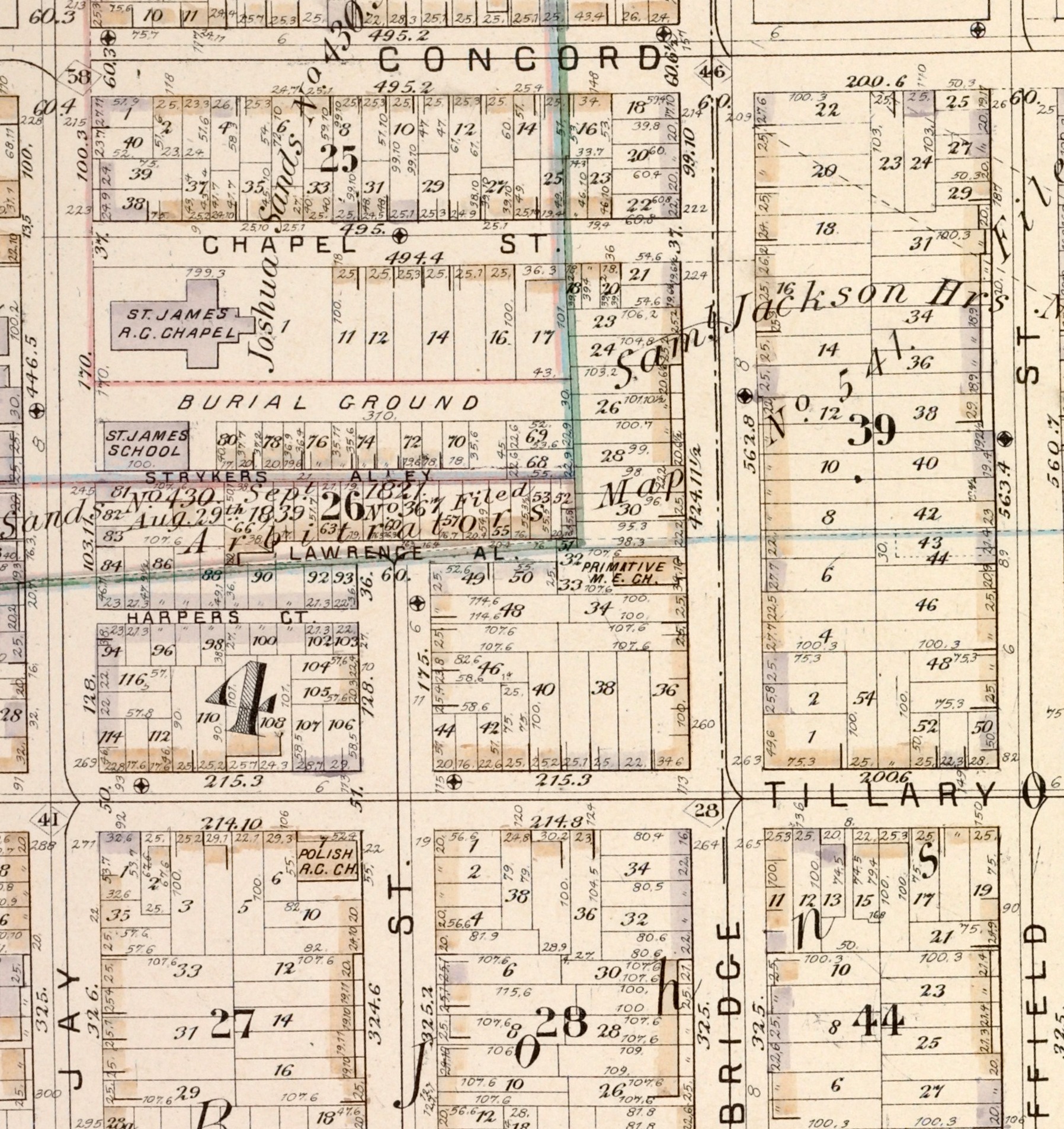

Located southeast of the St. James Cathedral on Jay Street, the alleyway was originally called Lyon’s Place (image below). Entrance to this narrow street was accessed from Tillary Street and it later acquired the name “Lawrence Place” possibly after the Civil War. It was renamed “Hennessy Place” in the early 1900s, and is now called “Cathedral Place,” but a portion of what used to be Lawrence Place no longer exists as a residential area as it is now the site of McLaughlin Park.

Portion of Plate 13 of Map of Brooklyn, 4th Ward by William Perris, engineer, published in 1855.

By 1870, with the end of the Civil War, the population of the City of Brooklyn would grow by approximately two hundred percent since the start of the war in 1861. If maps are any indication of growth, we can see the population influx as illustrated in the sheer number of buildings erected in a one block radius. Although Hopkins’ 1880 map (image below) was made four years after the demise of Sidney Evans, it helps to illustrates how densely populated his former neighborhood had become as compared to Perris’ 1855 map (image above). It is in this melting pot that we find Sidney Evans trying to find his niche, whatever that may have been.

Portion of Plate D in Detailed Estate and Old Farm Line Atlas of The City of Brooklyn as published by G.M. Hopkins and Co. in 1880

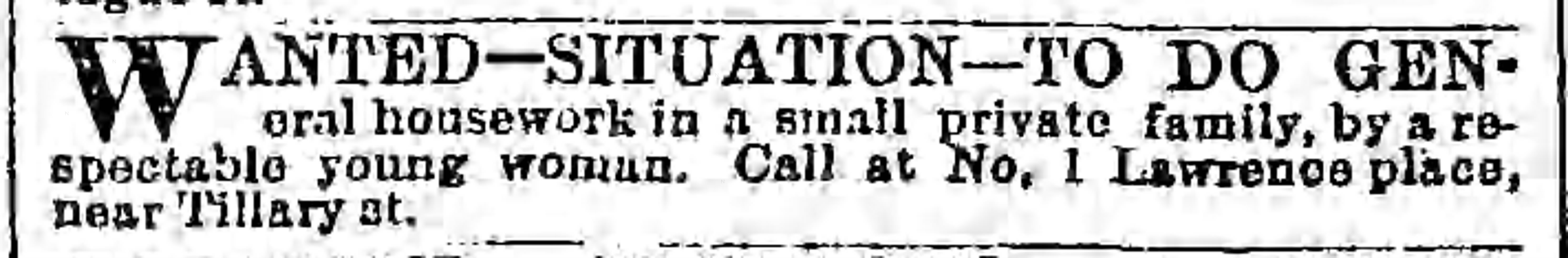

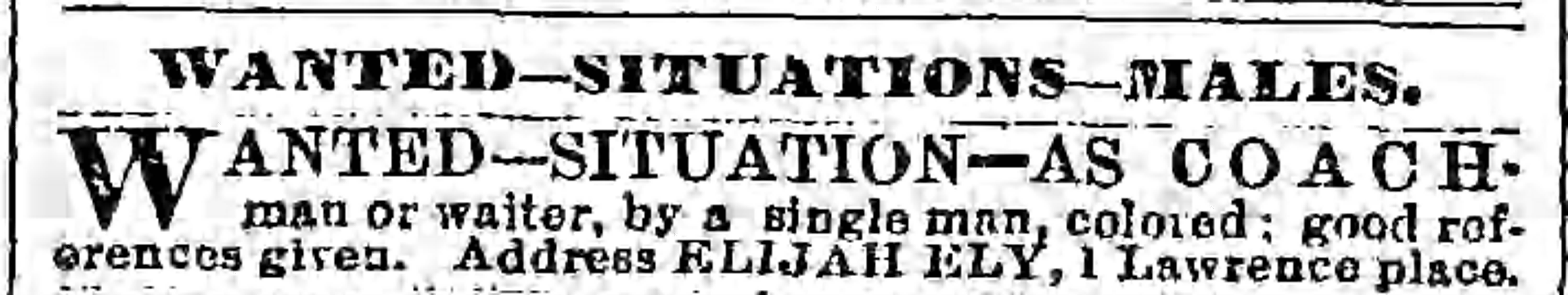

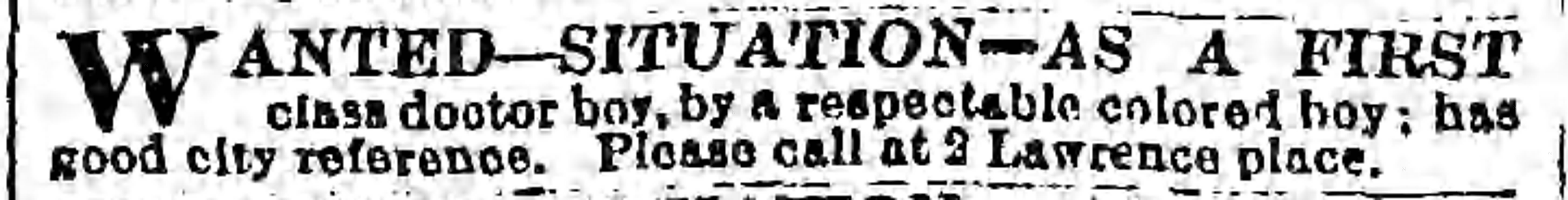

It is hard to narrow down what exactly “laborer” meant in 1875 in Brooklyn, but young people could always find work in such a diverse city. Here are examples of advertisements for employment by someone living at Lawrence Place:

WANTED – SITUATION – To Do General housework in a small private family, by a respectable young woman. Call at No. 1 Lawrence place, near Tillary st.

WANTED–SITUATION–As Coachman or waiter, by a single man, colored; good references given. Address ELIJAH ELY, 1 Lawrence place.

WANTED–SITUATION–As A First class doctor boy, by a respectable colored boy; has good city reference. Please call at 2 Lawrence place.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 2, 1876, page

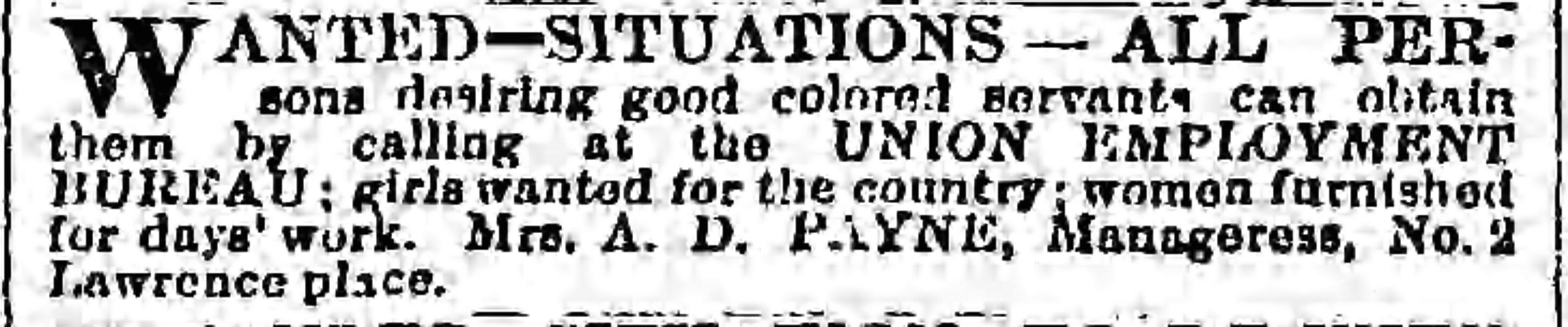

And those who could not find jobs on their own, would always be able to rely on services of an employment agency, such as one run by Sidney Evans’ neighbor, Mrs. Delia Payne:

WANTED–SITUATIONS–All Persons desiring good colored servants can obtain them by calling at the UNION EMPLOYMENT BUREAU; girls wanted for the country; women furnished for days’ work. Mrs. A.D. PAYNE, Manageress, No. 2 Lawrence place.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 13, 1876, page 3

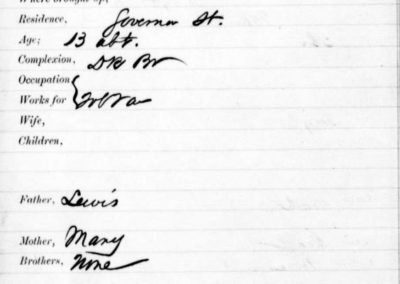

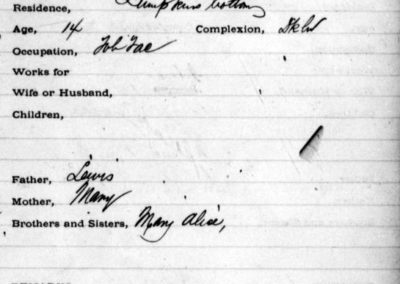

When following the trail of records from New York to Virginia, we find one possible connection to our Sidney Evans. A name appears twice in records of the Freedman’s Saving and Trust Company, an institution which was established by the federal government at the end of the Civil War. Colloquially known as “Freedman’s Bank,” it allowed former slaves and African-American Veterans of the Civil War ability to have financial stability. The bank closed its doors in 1874, but its records have been preserved and are now available to the public. Among these records, we find two names, spelled both as Sydney Evans and Sidney Evans, whose vital information confirm as describing the same individual (images below).

According to the Freedman’s Bank records, Sidney Evans was born sometimes in 1858 in Richmond, Virginia to Lewis and Mary Evans. He had a sister, whose full name may have been Mary Alice Evans, though her age was not indicated in the records. Between August of 1871 and January of 1872, Evans lived in the vicinity of Virginia State Capitol in Richmond and worked in one of the tobacco factories located a mile away. East of the capitol was Governor Street, which is still located there, and further east was the site of “Lumpkin’s bottom”, both of which were listed as place of residence for Evans.

A residence notation in the 1872 Freedman’s Bank record referred to area which included Lumpkin’s Jail, one of the places in Richmond with the darkest history. Named after slave trader Robert Lumpkin (1805-1866), the jail was built in 1830 at Shockoe Bottom. On November 27, 1844, Lumpkin became the third and last owner of the jail, but his notorious prominence forever etched his name to this place.

| Freedman’s Saving and Trust Company | ||||||

| Account No. | Date of Record | Name | Age | Date/Place of Birth | Residence | Occupation |

| 3419 | August 5, 1871 | Sydney Evans | about 13 years | 1858, Richmond VA | Governor Street | Tob[aco] Fac[tory] |

| 4198 | January 27, 1872 | Sidney Evans | 14 years | 1858, Richmond VA | Lumpkin’s bottom | Tob[aco] Fac[tory] |

At the close of the Civil War, Lumpkin’s Jail was turned into a school. According to the history of the Virginia Union University, Dr. J. G. Binney was the first teacher sent to Richmond by the American Baptist Home Mission Society. He had twenty five freed men as students between the period of November 1865 and July 1866, at which time he left the country for missionary work. On May 13, 1867, Dr. Nathaniel Colver came to Richmond to teach “Grammar, Arithmetic, Geography and Spelling/Reading as well as Biblical Knowledge.” Dr. Colver had rented the space for his school from Robert Lumpkin’s widow, a woman by the name of Mary, who herself was a former slave. In 1868, the Colver Institute, as the school came to be known, had a new principal, Dr. Charles Henry Corey, who “proved to be a dynamic leader and directed the school for 31 years, becoming revered by his students and earning the respect of the Richmond Community.”

In 1870, Dr. Corey moved the school out of Lumpkin’s Jail. Mary Lumpkin (1832-1905), who bore several children to Robert, would sell the land along with its buildings in 1873 to Mr. and Mrs. Ford. The jail itself was demolished in 1876, but the property also included “Lumpkin’s house, a boarding house for buyers and sellers [and] a kitchen/tavern building.” When Sidney Evans listed his place of residence as “Lumpkin’s bottom” in 1872, he could have referred to the two story building that was the jail, but he could have also been living in one of the other buildings. It is not far fetched to consider the possibility of Mrs. Lumpkin using both the jail and other buildings as a boarding house between the time when Colver Institute vacated the premises and her disposition of the property. And perhaps, Sidney Evans lived there until 1873 at which time he would collect all his savings from the tobacco factory and seek his fortunes further north, in Brooklyn, New York.

A History of the Richmond Theological Seminary by Charles H. Corey, page 47

Yet, the question remains as to the origins of our Sidney Evans. Is the Sidney Evans recorded in the Freedman’s Bank records the same Sidney Evans who perished at the Brooklyn Theater Fire? With all the discrepancies between records in New York and Virginia, can we be sure that we are tracing the life of the same Sidney Evans? If the reader reviews the 1871 record above and notes the phrase “Cannot Write” in place of Sydney Evans’ signature, all the instances of discrepancies between the records become apparent. It is likely that our Sidney Evans was born in slavery and even after his emancipation never obtained the basic forms of education. Could he have added added a few years to his age when he made the move from Richmond to Brooklyn in order to present himself as more experienced? We can only guess; and census record may provide even more clues about our Sidney.

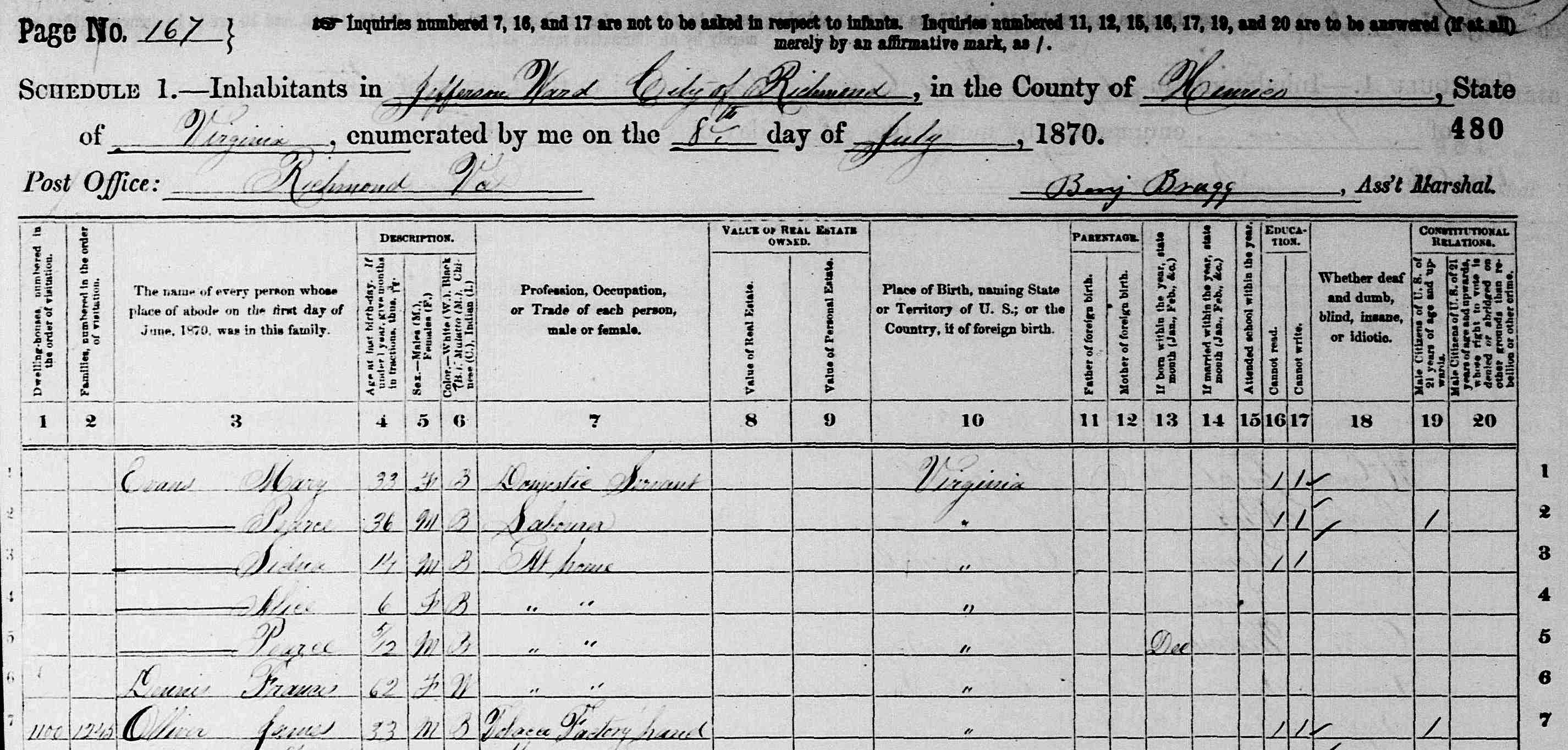

When the Ninth United States Census was enumerated for the City of Richmond on July 8, 1870, we find a certain “Sidna” Evans living with other members of his family in the household of Major Alfred Ranson Courtney (1833-1914). The census record shows a 33 year old Mary Evans as domestic servant for the Courtneys and with her: Pearce Evans (36 years), Sidna Evans (14 years), Alice Evans (6 years), Pearce Evans (5 months old), and an elderly white woman by name of Francis Dennis. Alas, no relationships were indicated in the census, so we surmise that if the 14 year old Sidna Evans is the same as our Sidney Evans, then the 33 year old Mary Evans was his mother, and 6 year old Alice was his sister. Furthermore, it is also possible that Sidney’s father’s full name was Pearce Lewis Evans, and the 5 year old Pearce, whose name was not mentioned in the Freedman’s Bank records, died in infancy.

Should we be allowed this conjecture, we would then have full account of our Sidney Evans’ origins.

Name: Sidney Evans (colored)

Age: abt. 25

Native of: U.S.

Resident of this City:

Occupation: laborer

Marital Status: single

Father’s Birthplace: U.S.

Mother’s Birthplace: U.S.

Place of Burial: Green-Wood Cemetery

Undertaker: Frank S. Henderson

Certificate of Death: 11293

[yuzo_related]

0 Comments