The Day When Brooklyn Burned

The Theater and the Play

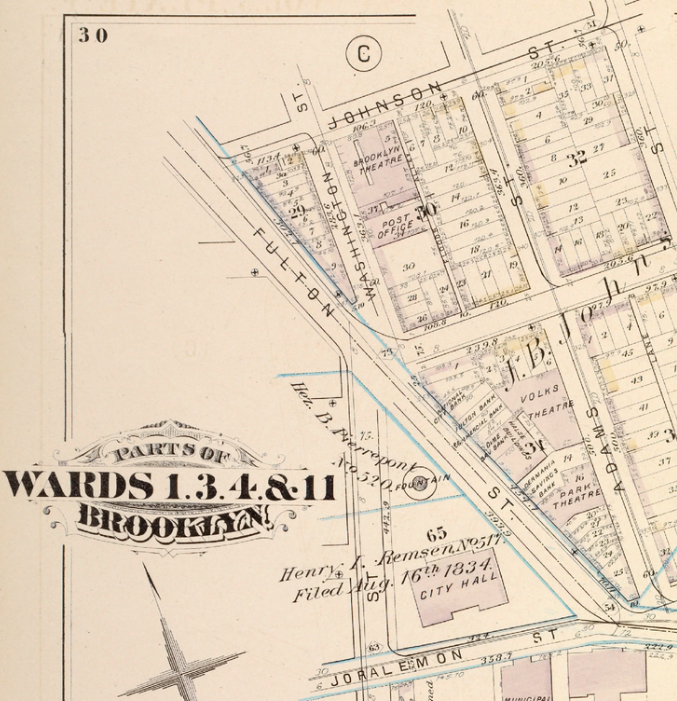

Talk around the town about Mrs. Conway’s new theater in Brooklyn began in the early months of 1871. Sarah Crocker Conway (1834-1875) and her husband, Frederick B. Conway (1819-1874), were successful managers of the Park Theater on Adams Street since 1864. They took over from the original proprietor, Mr. Gabriel Harrison, who had financial difficulties in running the theater since its doors opened a year prior. The Conways were successful enough that they required a new playground for their artistic abilities, and so the Brooklyn Theater was built on the corner of Washington and Johnson Streets, located diagonally from the Park Theater on Adams and Fulton Streets.

Portion of Plate F in Detailed Estate and Old Farm Line Atlas of The City of Brooklyn, published in 1880 by G.M. Hopkins and Co.

“Opening of the New House of Amusement” was announced in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. On October 2, 1871, “precisely at the hour of seven o’clock the doors were thrown open” and at “eight o’clock the curtain went up and discovered the full strength of the company standing upon the stage. ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ was sung…[and at] its close, Mr. and Mrs. Conway entered upon the stage, and, being recognized, they were accorded such a reception as but few public people receive in their lifetime.”

The opening play was Money, a comedy by English playwright Lord Lytton. “Of course, the house was crowded,” reported the Eagle, “and a greater number stood outside and watched the fortunate possessors of seats go in.” Such crowds at the Brooklyn Theater were hard earned by the determination of its proprietors, for theirs was a competition with many other “amusement houses” not only in Brooklyn but also in New York. Actually, the whole venture in the Brooklyn Theater, as was reported in Mrs. Conway’s obituary, “proved a disastrous investment. The class of audiences to which they now appealed again were slow to believe that as good performances could be given in Brooklyn as in New York.”

The fight to carve a niche in the theater world of Brooklyn proved too much for Mr. Conway; he withdrew himself from work as his health began to deteriorate by 1873. On September 6, 1874, Frederick Bartlett Conway died in Massachusetts and his body was brought to Brooklyn to be laid to rest in the Green-Wood Cemetery (Lot 16823, Section 167).

Brooklyn Theater is the second building (with mansard roof) to the left of post office (NYPL Digital Collections)

Three months later, the Union Theater in New York announced the production of a new play, The Two Orphans. The play was an adaptation by Naphtali Hart Jackson of New York from the French Les Deux Orphelines by Adolph D’Ennery and Eugene Cormon. The Union Theater was owned by Sheridan Shook and managed by Albert Marshman Palmer, the two men who commissioned Hart Jackson (who legally changed his name in 1876) for the English version of the play.

On April 12, 1875, Mrs. Conway, having obtained permission from Messrs. Shook and Palmer, staged the production of The Two Orphans in the Brooklyn Theater for the first time. On that day, Miss Lillian Conway, daughter of the proprietors, made her stage debut in the role of Louise, one of the orphans. “The play was played, and success followed. Mrs. Conway at last saw her dreams realized. She started to reach this goal. She reached it and died” on April 28, 1875, reported The Eagle. Children of the Conways became the new lessees, but within a year of their management they had to relinquish their interests in the Brooklyn Theater in favor of Messrs. Shook and Palmer.

On December 5, 1876, the evening issue of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a review of The Two Orphans from the previous night: on a scale as to human and mechanical interpretation, which certainly made a near approach to the common idea of perfection. The audience, although in point of numbers it was scarcely on a par with the claims of the occasion, was visibly moved during the progress of the play and must have left the theatre with an impression of the performance such as in itself ought to prove no bad advertisement of its excellence. The applause was frequent, hearty and spontaneous, and in response to it the curtain had to be raised after nearly every one of the seven tableaux, by which the action of the piece is articulated…The whole representation, therefore, was one which exacts the acknowledgement that little can be said of it except in the way of praise.

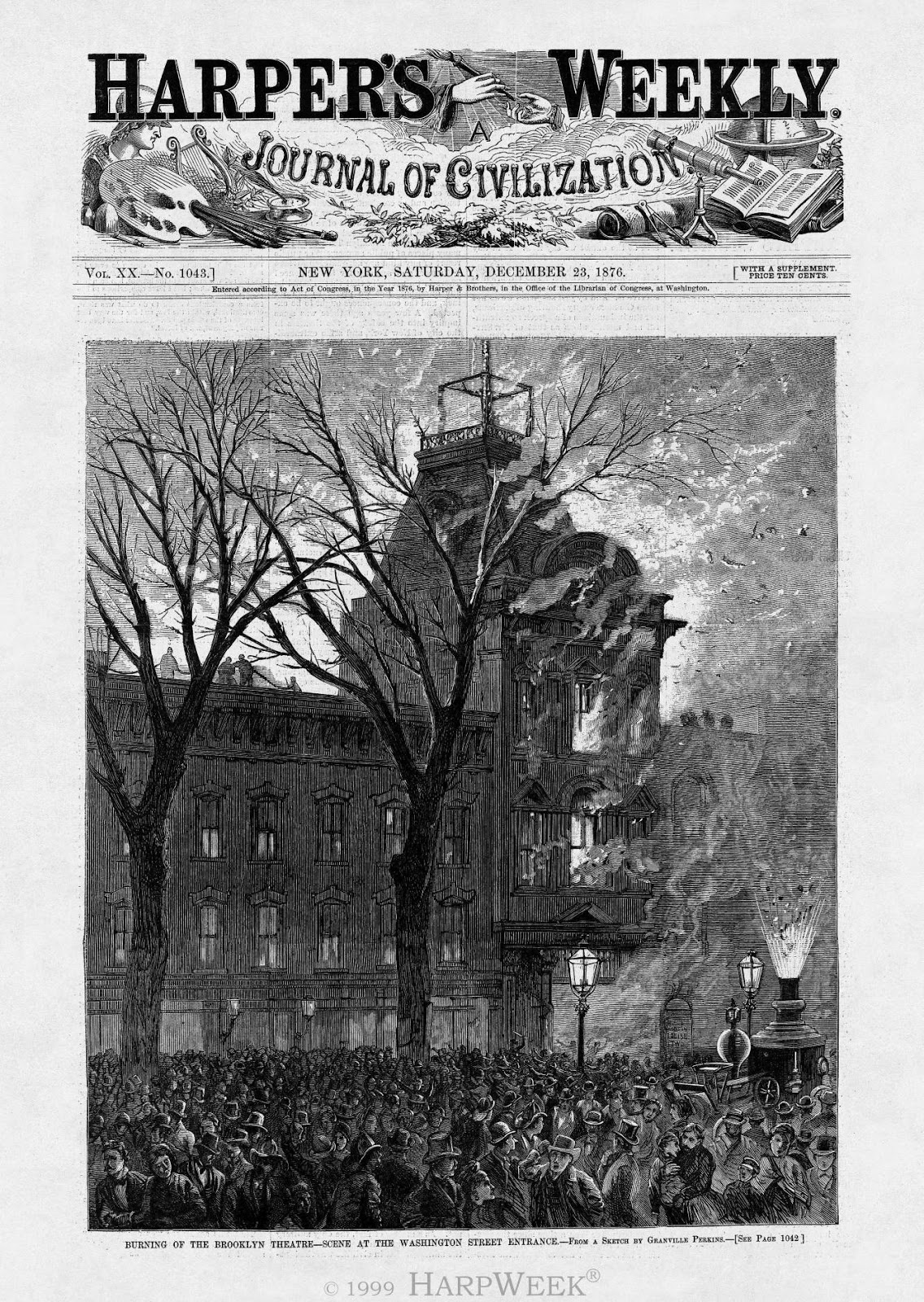

After a few hours the review was published, the doors of the Brooklyn Theater were opened once again for the audience. That night, the play took a different turn by the time it ended. At about 11:15 pm, just before the last act, the house curtains caught fire. In less than half hour, the entirety of the theater building was engulfed in flames.

Cover of the December 23, 1876 issue of the Harper’s Weekly

The Number of Victims

Of the primary sources of information, the newspapers are the most common, but they are secondary in accuracy compared to the official records. These included reports given by the coroner of the city of Brooklyn, Henry C. Simms; the fire marshall, Patrick Keady; and the Executive Committee of the Brooklyn Theater Fire Relief Association report. My goal is to explore these sources, which deal primarily with the victims. The most important of the above-mentioned is the coroner’s report.

In the panic that ensued immediately following the fire, local newspapers published updated lists daily, sometimes twice a day, as more people searched for their loved ones. The reporters had two sources of information: the place of the tragedy and the families of the victims. The list included the names of the dead found at the theater and the supposed victims who were reported missing by their families.

The Daily Argus printed a booklet titled The Holocaust at the Brooklyn Theatre with an alphabetical list of the victims. The paper claimed that it was “the only authentic roll of the missing and recognized dead” being compiled “from official sources” with the “names of the recognized bodies…indicated by an asterisk (*).” When all the names are tallied, there are 350 total, including 138 unrecognized names and 212 identified bodies. These figures differ from other published reports.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle published extensive reports of the fire giving detailed descriptions of the events leading up to it. For example, page four of the December 6, 1876 issue was exclusively devoted to the matters related to “The Calamity” and included the first list of the missing and injured individuals. The first list of the “Known to be Dead” included a dozen names: At this writing thirty bodies have been taken out, but the pile is still four to five feet deep on the floor of the cellar under the vestibule.

As excavations of the rubble continued, the morgue was near capacity, prompting the city to establish makeshift morgues at nearby markets and theaters. By day two, The Eagle ran conflicting headlines: “Two Hundred and Eighty Dead” on page two and “Two Hundred and Ninety Dead” on page four.

On December 8, three days after the fire, The Eagle reported that “THE HOLOCAUST” consumed the lives of two hundred and ninety-three individuals. The last list of victims reported by the Daily Eagle was in the December 9 issue, on the same day when the burial of the unrecognized bodies took place in a mass grave in the Green-Wood Cemetery. Of the reported names, the list contained 163 names of individuals for whom burial permits were issued by the coroner. There were also 83 names of “persons known or believed to have perished in the flames whose bodies have not been identified.” Some names however, appear on the list of those individuals who were given burial permits by the coroner.

Fire Marshal Keady lists 284 victims of the fire that included 102 “unknown bodies”. This list is identical in number as reported by the coroner. Henry C. Simms issued 186 certificates of deaths; of those, three were for unidentified victims, one for “100 bodies for burial,” and two certificates each for one unknown body; thus a total of 102 victims were unrecognized. Burial permits were issued for 285 individuals. One victim of the fire was inadvertently issued two copies of a death certificate, bringing the total number of victims to 284.

The link above shows a list of victims organized by their death certificate numbers. It is a .pdf file that can be downloaded and searched. It is important to note that there are gaps in the sequence of the certificates, e.g. between 11408 and 11424, whose records show cause of death other than fire at the Brooklyn Theater. Also, the last two individuals on the list, William Dench and John E. Cumberson, who were rescued, died a few days later from injuries sustained in the fire. Regarding the records of the unknown victims, the above list does not include the third certificate which was issued at the end of December for someone who was laid to rest in Green-Wood Cemetery on December 30, 1876.

And, last but not least, on one side of the granite obelisk that marks the site of the burial of the unknown victims in the Green-Wood Cemetery, the inscription reads: the remains of one hundred and three were buried in this plot with civic and military honors, on Saturday December 9, 1876. As the official records indicate, there were only 102 unknown victims, which is also confirmed by the records of the Cemetery. Moreover, remains of four known victims were also laid to rest in the mass grave with the unknowns as their burials were paid for by the City of Brooklyn. Therefore, there are a total of 106 victims buried “under the obelisk” in Lots 22427-22432 in the Green-Wood Cemetery.